Rugs and Sofa Cleaning: Why March is the Critical Month for Upholstery Care

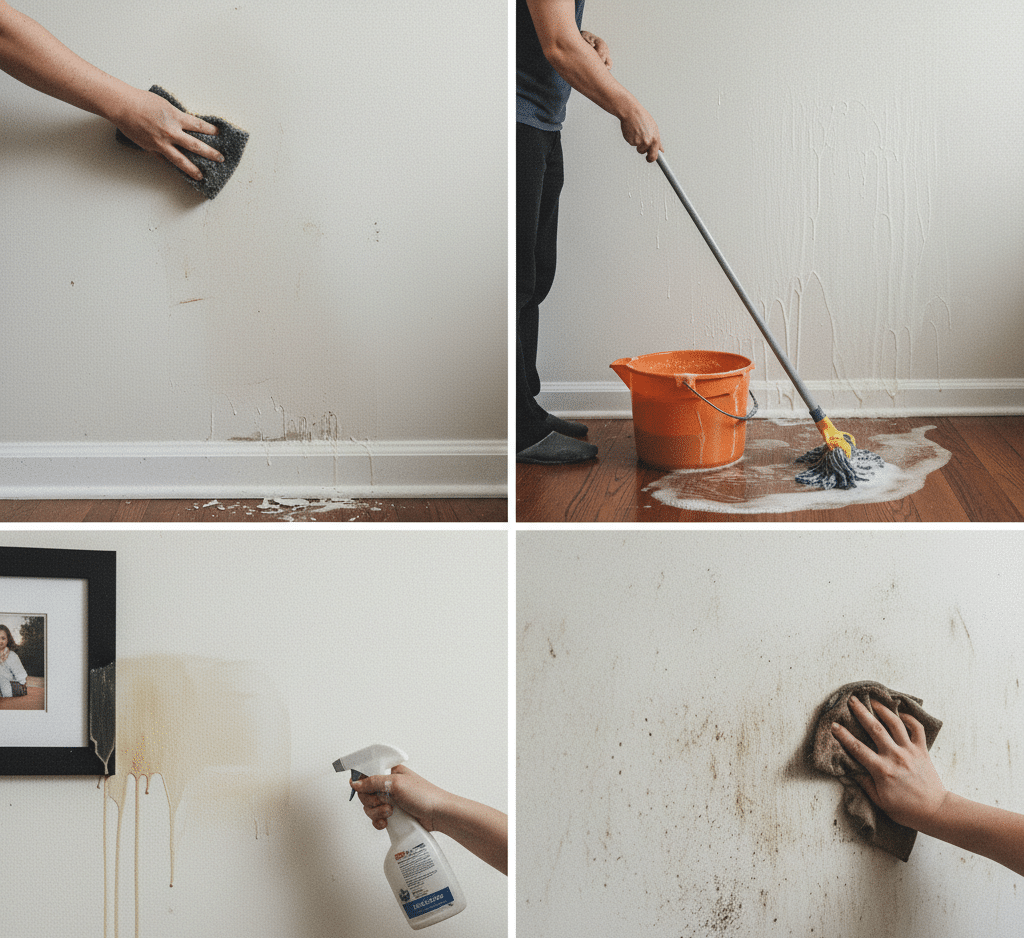

As the calendar turns toward March and the first genuine rays of spring sunlight begin to pierce the grey canopy of the Canadian winter, homeowners are often greeted by a stark and unflattering revelation. The sun, usually a welcome visitor, acts as a harsh spotlight when it hits the interior of a home that has been sealed tight against the cold for months. It illuminates the floating particulates in the air and casts a glare on the upholstery and flooring, revealing a dullness that was hidden by the ambient gloom of winter. During the cold months, our homes function as closed-loop ecosystems. We lock the windows and run the furnace, recirculating the same air repeatedly. In this environment, the soft furnishings—the wall-to-wall carpeting, the area rugs, and the upholstered sofas—cease to be mere decorations. They transform into giant, passive air filters. They trap the dust, the desiccated skin cells, the pet dander, and the microscopic debris that settles out of the stagnant air. By the time spring arrives, these items are not just dirty; they are saturated “dust sponges” that require a deep, restorative recovery to transition the home from a state of hibernation to a state of health. Vacuum Cleaner To understand the necessity of this recovery process, one must first recognize the limitations of the standard weekly vacuuming routine. While vacuuming is an essential maintenance task, it is strictly a surface-level intervention. A vacuum cleaner relies on suction and airflow to lift loose debris from the top layer of the carpet pile or the fabric weave. It is excellent at removing crumbs, pet hair, and surface dust. However, it is largely ineffective against the deep-seated particulates that have migrated to the base of the fibers. Gravity and the pressure of foot traffic drive grit and soil down to the backing of the carpet, where the vacuum’s airflow cannot reach. This trapped grit is not dormant; it is abrasive. Every time you walk across the rug or sit on the sofa, these sharp, microscopic particles grind against the base of the fibers like sandpaper. Over time, this friction cuts the fibers, leading to the premature baldness or “fuzzing” seen in high-traffic areas. Vacuuming manages the aesthetic, but it does not arrest this structural degradation. A specific and often baffling phenomenon that manifests after a long winter is known as filtration soiling. Homeowners often notice dark, greyish lines appearing around the perimeter of a room, underneath baseboards, or under closed doors. There is a common misconception that this is caused by a vacuum cleaner failing to reach the edge. In reality, it is a physics problem related to airflow. In a home with a forced-air heating system, air is constantly moving from areas of high pressure to areas of low pressure. When the furnace blows warm air into a room, that air seeks an escape route. It often finds it through the tiny gaps between the floorboards and the wall, or under a door. As the air is forced through the edge of the carpet to escape, the carpet acts exactly like a HEPA filter. It traps the microscopic pollutants—carbon soot from candles, road dust, and fine particulate matter—carried in the air. The resulting dark line is a concentrated deposit of oily, airborne soil that has chemically bonded to the carpet fibers. This is not dirt that can be vacuumed away; it is a stain caused by the house breathing through its floor. Sweat, Oils and Creams The composition of the soil trapped in your upholstery adds another layer of complexity. Unlike a hard floor, which allows dirt to sit on the surface, fabric absorbs. Throughout the winter, we spend more time indoors, often lounging on sofas and chairs. The fabric absorbs body oils, perspiration, and the lotions we use to combat dry winter skin. These oils act as a binder. They coat the fibers of the sofa and the rug, making them sticky. When dust settles on an oily fiber, it does not just sit there; it adheres. This creates a dull, heavy appearance that vacuuming cannot resolve because the dust is glued to the fabric. This sticky matrix also becomes a breeding ground for dust mites. These microscopic arachnids feed on dead skin cells, and in the warm, humid microclimate of a sofa cushion, their populations can explode. The waste products they produce are potent allergens. When you sit on a dusty sofa, you compress the cushion, acting like a bellows that puffs these allergens into the air you breathe. Recovering your textiles from this winter load requires a shift from maintenance cleaning to extraction cleaning. This is the fundamental difference between moving dirt around and removing it from the building. Spot cleaning, which is the go-to method for many homeowners dealing with a spill, is often detrimental when applied to general soiling. When you spray a detergent on a sofa armrest and scrub it with a cloth, you are essentially creating a mud slurry. You might lift some of the dirt onto the cloth, but much of the detergent and the dissolved soil is pushed deeper into the foam padding. Furthermore, the detergent residue left behind is sticky. It will attract new dirt faster than the surrounding area, leading to a phenomenon where the “cleaned” spot eventually turns blacker than the rest of the furniture. Extraction Cleaning Extraction cleaning, specifically hot water extraction (often mislabeled as steam cleaning), is the only method capable of breaking the bond between the oil, the dust, and the fiber. This process involves injecting hot water and a specialized cleaning solution into the carpet or upholstery under high pressure. The heat liquefies the body oils and sticky residues, while the pressure agitates the deep-seated grit. Crucially, this injection is immediately followed by high-powered vacuum extraction. The machine pulls the water, the detergent, and the suspended soil out of the fabric and into a waste tank. It is a flushing mechanism. It resets the chemical balance of the fiber, leaving it neutral

Rugs and Sofa Cleaning: Why March is the Critical Month for Upholstery Care Read More »