Medicine Cabinet: 5 Amazing Organization Tips for Shared Bathrooms and Medicine Cabinets

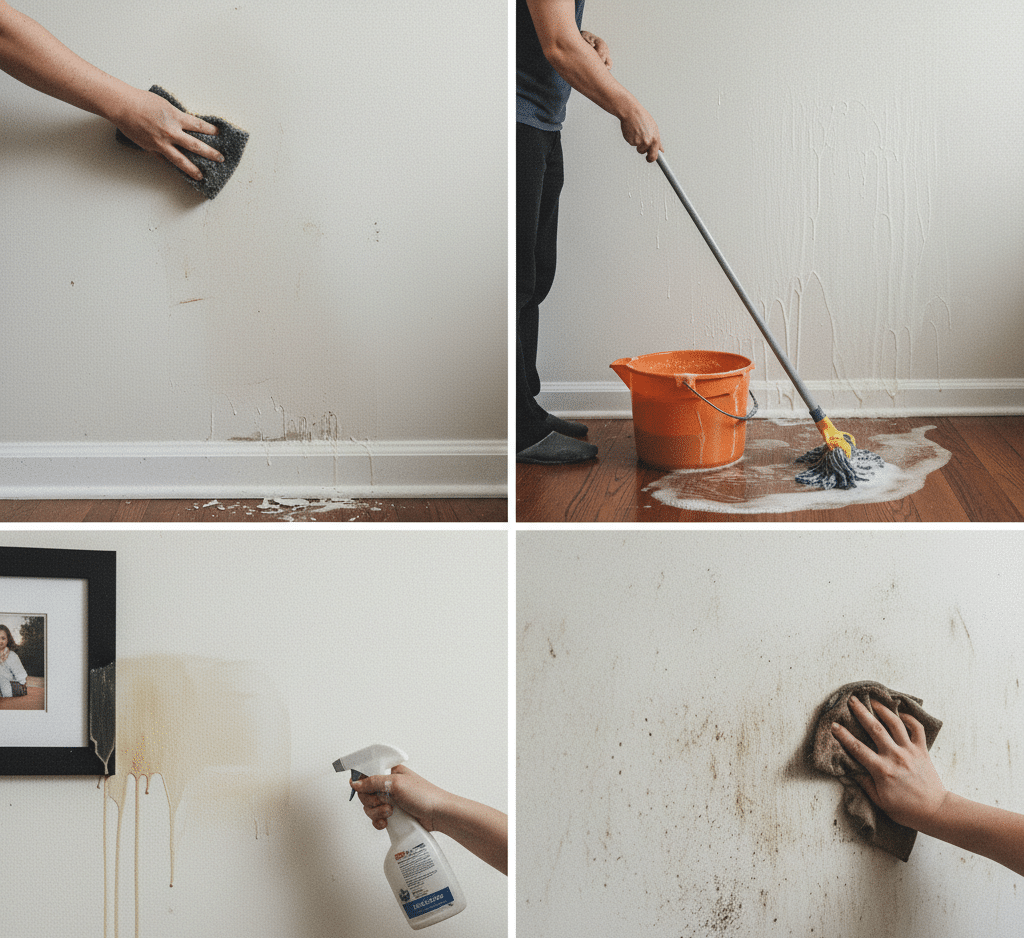

The medicine cabinet is arguably the most utilitarian few square feet in the entire home. Hidden behind a mirror, it acts as the nerve center for our daily rituals of hygiene, grooming, and health management. It is the first thing we confront in the morning as we brush our teeth, and the last thing we close before bed. Yet, despite its central role in our lives, this vertical storage space is frequently a disaster zone of expired prescriptions, sticky cough syrup bottles, rusted tweezers, and half-empty tubes of toothpaste. This chaotic jumble is not merely an organizational failure; it is a source of daily micro-stress and a potential health hazard. When you are ill, injured, or rushing to get ready for work, the inability to find what you need immediately adds friction to a moment that requires fluidity. Transforming the medicine cabinet from a graveyard of forgotten products into a streamlined, functional dispensary requires a systematic approach that balances spatial logic with safety protocols. Emptying the Cupboard To begin the reorganization process, one must strip the architecture down to its bones. The first step is total evacuation. You cannot organize a cabinet while it is full. Remove every single item and lay them out on a clear surface, such as the bathroom counter or the dining table. This visual inventory is often shocking. We tend to accumulate health and beauty products in a linear fashion, buying new ones before the old are finished, or stocking up on remedies for a flu that happened three years ago. With the shelves bare, take the opportunity to deep clean the interior. The medicine cabinet is a magnet for a specific type of grime: rings of rust from metal cans, sticky residues from leaking liquids, and a dusting of powder from cosmetics. Scrub the shelves—often made of glass—with a glass cleaner or a vinegar solution to restore their transparency. If the shelves are adjustable, remove them to clean the tracks and the back wall, ensuring the canvas is pristine before any item returns. The auditing phase is the most critical component of this project, and it is where safety takes precedence over thrift. You must become a ruthless editor of your own inventory. The primary target is expiration dates. Medications, both over-the-counter and prescription, degrade over time. Their chemical stability falters, rendering them ineffective or, in some rare cases, toxic. A bottle of aspirin from 2018 will not help your headache today. Sunscreen expires and loses its SPF protection. Antibiotic ointments separate and lose potency. Inspect every crimped tube and every bottle bottom. If it is expired, it must go. However, disposal requires responsibility. Flushing pharmaceuticals down the toilet is an environmental error, as these chemicals can contaminate the water supply. Many pharmacies offer take-back programs for old drugs, which is the only responsible way to discard them. Beyond the dates, you must assess the utility of the remaining items. Do you actually use that shade of lipstick? Is that jar of expensive face cream from two years ago now smelling rancid? Cosmetics harbor bacteria. Mascara, specifically, has a short shelf life of about three months before it becomes a risk for eye infections. If a product smells off, has changed color, or has separated into oil and solid layers, it belongs in the trash. The goal is to curate a collection of items that serve your current life, not the life of the person you were five years ago. Strategic Reloading Once the purge is complete, the strategic reloading of the cabinet begins. The fundamental flaw in most medicine cabinets is the lack of vertical zoning. We tend to treat the shelves as equal, but they are not. The prime real estate is the shelf at eye level. This zone should be reserved exclusively for the “daily drivers”—the toothbrush, the deodorant, the daily contact lenses, and the skincare regimen used every morning and night. By placing these high-frequency items in the most accessible spot, you streamline your routine and reduce the likelihood of knocking over other bottles to reach them. The upper shelves, which often require a slight stretch to reach, are the appropriate home for “occasional” items. This is where the first aid supplies, the weekly face masks, and the backup razors belong. You need them to be accessible, but you do not need them to compete for your attention at 7:00 AM. The highest shelf, often difficult to see, should be reserved for dangerous items if there are children in the home, or for bulk refills that are rarely accessed. Conversely, the lowest shelf is ideal for heavier items or things that might drip, ensuring they don’t ruin everything below them. However, there is a scientific nuance to medicine cabinet organization that contradicts its very name. The bathroom is actually the worst place to store medicine. The environment of a bathroom is defined by fluctuating temperatures and high humidity. Every time you take a hot shower, the room fills with steam. This moisture seeps into the cabinet, condensing on bottles and penetrating non-airtight containers. Heat and humidity accelerate the degradation of pills and capsules. They can cause aspirin to break down into vinegar (acetic acid) and can alter the chemical structure of prescription drugs. Ideally, true “medicine”—your antibiotics, your heart medication, your pain relievers—should be relocated to a cool, dry place, like a kitchen cabinet away from the stove or a dedicated box in the bedroom closet. The bathroom cabinet should be rebranded as the “grooming cabinet,” housing only those items that are stable in humidity, such as toothpaste, mouthwash, and sealed lotions. Organization If you must keep certain remedies in the bathroom for convenience, such as band-aids or antiseptics, storage solutions are vital to protect them. The original cardboard packaging of most products is the enemy of organization. Boxes are bulky, they crumble in humidity, and they obscure how much product is left. Decanting items or removing them from their boxes is a powerful space-saving tactic. Blister packs of

Medicine Cabinet: 5 Amazing Organization Tips for Shared Bathrooms and Medicine Cabinets Read More »